Over the past few years, I’ve become increasingly interested in the creative jazz that emerged from California from the 1950s to the 1980s. The most important proponents of the avant-garde out West were musicians like Jimmy Giuffre, Ornette Coleman, Horace Tapscott, Vinny Golia and the Cline Brothers.

Two of the most important figures in the progressive jazz scene were multi-reedist John Carter and trumpeter/cornetist Bobby Bradford. During the mid to late 1960s, this forward thinking duo came together to help form the New Art Jazz Ensemble and remained close collaborators until Carter’s death in 1991.

Through the whims of legendary record producer Bob Thiele, Carter and Bradford were given a chance to present their unique style of jazz to a larger audience. They released two outstanding recordings, Flight of Four and Self Determination Music on Thiele’s Flying Dutchman label in 1969 and 1970. The recordings did not make the tandem household names but they did firmly entrench them as standard bearers of the new music on the West Coast.

I recently had the good fortune to speak with Mr. Bradford about these two recordings and the events that led up to their creation. Through Mr. Bradford’s memories and a bit of research, I was able to gain some insight into the music.

John Carter

|

| Carter |

Carter started playing professionally at 14 after he had picked up the saxophone and flute. Carter’s association with saxophonist Ornette Coleman and drummer Charles Moffett began in the 1940s as bebop zealots but, as there was no work for jazz musicians, they all played as part of the R&B scene of middle Texas.

Carter was a brilliant young man. He graduated high school at the age of 15 and attended Lincoln University in Jefferson, Missouri, where he received his Bachelor’s of Arts in 1949 (just 19 years old). While he attended Lincoln, Carter continued to play and tour infrequently, mostly with Kansas City based blues musicians like George Baldwin. Carter continued his education at the University of Colorado where he received his Masters in 1956. Between 1949 and 1961, Carter found work by teaching music in the public schools of Ft. Worth.

In 1961, Carter relocated to Los Angeles with his wife, with whom he would have four children. He was able to find work as a traveling music teacher, driving from school to school. Carter had originally wanted to try his hand as a studio musician but found that the sacrifice wouldn’t be worth it – studio work would have consumed all his time and wouldn’t have let him focus on his own individual musical development.

Carter maintained a busy schedule as an educator but still played as frequently as he could. He knew and performed with many of the Los Angeles based musicians, including pianist Hampton Hawes and saxophonist Harold Land. By the 1960s, Carter had begun looking for new musicians that were interested in the new directions he had been exploring. It was his friend Ornette Coleman that recommended Bobby Bradford.

Bobby Bradford

Bobby Lee Bradford was born July 19, 1934 in Cleveland, Mississippi. He spent his early childhood in Mississippi. Unlike Carter, Bradford’s relocation to California took a few attempts to hold.

The first was by car in 1944 when Bradford’s stepfather, mother and brother went to look for better opportunities out West. His stepfather’s brother had already established himself in California and work at the Douglas aircraft manufacturer looked promising – ultimately it wasn’t. After a brief spell in Detroit right after the unsuccessful Los Angeles try, Bradford decided that he didn’t see eye to eye with his stepfather and moved to Dallas to settle in with his father at the behest of his mother. This was in 1946 and he was 11 1/2 years old.

|

| Bradford |

The Dallas and Ft. Worth jazz scene was expansive at that time. It wasn’t until Bradford was a freshman at Samuel Huston College in Austin, Texas that he finally played with that “Ft. Worth musician who was doing some far out shit.” The occasion was Bradford’s friend and drummer Charles Moffett’s wedding. A jam session was set up to celebrate at the Victory Grill in Austin. That was where Bradford first heard Moffett’s best man, the saxophonist Ornette Coleman.

Bradford’s next rendezvous with Coleman wouldn’t occur until he left college after a year and a half for Los Angeles in 1953. Bradford hadn’t been getting what he wanted out of Huston College and decided to try his luck out West. He settled in with his mother and stepfather. It wasn’t long after his move that Bradford met Coleman on the Red Car, a train that ran between Long Beach and downtown Los Angeles.

Bradford’s next rendezvous with Coleman wouldn’t occur until he left college after a year and a half for Los Angeles in 1953. Bradford hadn’t been getting what he wanted out of Huston College and decided to try his luck out West. He settled in with his mother and stepfather. It wasn’t long after his move that Bradford met Coleman on the Red Car, a train that ran between Long Beach and downtown Los Angeles.

Coleman had moved to Los Angeles after leaving the Pee Wee Crayton band. When Bradford met him, the saxophonist had already married poet Jayne Cortez and was living at her parents’ home. Coleman was interested in playing with Bradford but was also looking for employment, which Bradford was able to help him with. Bradford was working as a stock guy at Bullock’s department store and was able to get Coleman a position there.

The two musicians met frequently at Coleman’s in-law’s house to practice. Coleman and Cortez moved shortly thereafter to an apartment over a commercial garage where the musicians had more opportunity to play their music.

Coleman and Bradford were able to find gigs every so often playing bebop and Tin Pan Alley tunes in the red light district of Los Angeles, including a number of gay bars. While his concepts weren’t fully realized, Coleman had begun adding his own tunes to the group’s repertoire though the group played mostly tunes with chord changes.

|

| Ornette Coleman |

Bradford received his draft notice in 1954. He volunteered which allowed him to opt for either the Air Force or Navy for a span of 4 years. He chose the Air Force and reported for service on December 28, 1954. Bradford spent those four years playing in the jazz band, where his technique “went up 200 percent.”

By this time, Bradford was married with twin boys and a young daughter. He decided to return to school to finish his degree so that he could teach music. Bradford enrolled at the University of Texas in Austin where he attended for one year and a semester. The University was on the other end of town and proved to be a hassle to get to between work and family obligations.

Bradford was then offered an opportunity for a scholarship at Huston-Tillotson University. Huston College had merged with Tillotson College in 1952. The proximity made it much easier for Bradford. For their scholarship, Bradford had to be a “music gofer” - playing in every ensemble while maintaining his job at a local bowling alley.

Professional opportunities didn’t dry up while Bradford was at Huston-Tillotson, in fact, though he had to turn many down. Coleman called in 1960 to ask Bradford to play on his Free Jazz album (Atlantic SD 1364, 1961). Bradford asked the University administration if he could leave but as it was the middle of a semester, he would have received an incomplete. His absence prompted Coleman to use trumpeter Freddie Hubbard in his stead.

Broke during the spring of 1961, Bradford decided to join up with Coleman in New York City. Contrary to many reports, Coleman was still playing frequently but not recording beyond his own rehearsal tapes. The saxophonist had put together a new ensemble due to a falling out with trumpeter Don Cherry, whom Bradford replaced. There were auditions for bassist and drummer, the spaces eventually going to Jimmy Garrison and Charles Moffett respectively.

The new ensemble opened at the Five Spot during the summer of 1961 with all new music. The group played regularly throughout the summer and fall of that year all over New York City, including the original Jazz Gallery (where there was an art exhibition running concurrently) and Birdland. The only gig that Bradford recalled outside of NYC was a single hit in Cincinnati, Ohio where Coleman introduced his Free Jazz Octet that featured Bradford and Don Cherry, soprano saxophonist Steve Lacy, bassists Garrison and Art Davis and drummers Moffett and Ed Blackwell. (Apparently there are rehearsal recordings of this group, nothing more).

Bradford continued to travel between New York and Texas, playing music on the weekends while working a day job and going to school the rest of the week. Bradford didn’t do much playing outside of the Coleman ensemble, though he occasionally played in Latin dance bands - what he called “pre-salsa” bands. He tried bringing his family to New York shortly but Coleman began his boycott of the local club scene that left Bradford out of work and forced him to return to Texas. Bradford’s family had moved into a Federal Housing Project in Austin, just able to survive on his modest income.

In May of 1963, Bradford graduated from Huston-Tillotson. He immediately got a job teaching music at a school in Crockett, Texas. It wasn’t long until he decided to try his luck in California again. Bradford packed up his family and moved back in 1964.

When he arrived in Los Angeles, Bradford found work as a workman’s comp adjuster for Los Angeles County. The County made him report in San Bernadino, which was far from his Los Angeles home. The family eventually settled in Pomona, closer to work.

The twain shall meet…

It was a few years before Carter and Bradford met. After playing with numerous groups and a hectic teaching schedule, Carter was looking for something new. He was a good friend of Ornette Coleman from his days in Ft. Worth; Carter even conducted Colemans’s first symphonic work “Inventions of Symphonic Poems” in May 1967 at the UCLA Jazz Festival.

Carter asked Coleman for a player recommendation; Coleman recommended Bradford and gave Carter Bradford’s phone number. The two had known of each other while in Texas but had never met.

In an interview with Frank Kofsky in Jazz & Pop (Vol 9, #1 – Jan. 1970) Carter recalled: “I was interested in getting a thing going, and Ornette said, well, you and Bobby Bradford ought to get together because Bobby Bradford is here in California somewhere. But he didn’t know where Bob was at the time, so he called to Texas, to a mutual friend of ours, and he had Bob’s brother’s address, phone number, so I called him. Bob and I finally got together like that, and were already working by the time of the big band thing at UCLA, in 1966.”

Bradford assumed that the “big band thing” was the Coleman work at the jazz festival mentioned above. That occurred in 1967 and did not involve Bradford.

Carter called Bradford shortly after and the two hooked up. Carter lived in Los Angeles with his family while Bradford’s was in Pomona. Rehearsals would require a long commute. One rehearsal space they found was a studio that was opened on 103rd Street and Grandee Avenue for the local black community after the Watts riots of August 1965. It was interesting to note that a large portion of the studio’s funding came from actor and liberal philanthropist Larry Hagman, who would later portray the inscrutable conservative J. R. Ewing on the television sitcom Dallas.

Carter and Bradford began to audition rhythm section players in order to form an ensemble. Carter knew many of the musicians around town and was able to put his feelers out. The two recruited drummer Eldridge “Bruz” Freeman (brother of saxophonist Von and guitarist George Freeman from Chicago) and bassist Tom Williamson. The resulting group was named the New Art Jazz Ensemble.

Gigs were hard to come by in and around Los Angeles.

|

| NAJE - Williamson, Carter, Bradford & Freeman |

From the Frank Kofsky interview in Jazz & Pop (Vol. 9, #1):

Carter: First of all, there’s no place for exposure. We’ve been playing where we’re playing – in the ghetto – for a long time. There are only three jazz clubs in the town.

Kofsky: Why do you suppose you can’t get booked into clubs?

Bradford: First of all, if we were playing straight up-and-down kind of jazz, it would help. But playing what we’re playing, and not being the kind of music that the mass of people are going to rush into the club to hear, the club owner – being concerned with having a group there that a crowd of people are going to come to hear – is not prepared to take any kind of chance on a group like ours, where, if an owner is going to take a chance, they’d rather take it on a group that at least they are personally happy with.

New York Times critic Robert Palmer had this quote from Carter in a 1982 article about the duo and their collaboration since the 1960s:

In 1969, when the quartet led by Mr. Carter and Mr. Bradford had already been together for two years, the trumpeter picked up a drinking glass and remarked to a friend, “You could put all the money this group has made in the last two years – in nickels – in there and not even reach the top.” (April 30, 1982, p. C16)

|

| Ray Bowman |

It might have been at the Century City Playhouse that John Hardy heard the NAJE. Hardy would soon be the first to record the group.

John Hardy was a biology professor at Occidental College, ornithologist and co-owner of the independent jazz label Revelation Records. Hardy invited the NAJE to perform and record at Occidental on January 16, 1969. The ensemble performed to an audience in the College’s Herrick Lounge. There was no money advance but the group was willing to make the recording for the exposure.

Seeking (REV-9, 1969) was released in the spring on Revelation. The group didn’t make any money but had a recording to their name. The initial announcement of the upcoming recording was made in the March 6, 1969 issue of DownBeat (Vol. 36, #5) along with the group’s performance at the Cal State Jazz Festival. The March 20, 1969 issue (Vol. 36, #9) showed that the ensemble had played at Shelly’s Manne Hole for three nights.

Reviews for Seeking were very good. They included a 4 ½ star review by John Litweiler in the September 19, 1969 issue of DownBeat (Vol. 36, #19). Litweiler was especially impressed by Bradford’s playing but was concerned that the ensemble’s aural proximity to Ornette’s efforts might ultimately hinder their success.

Reviews for Seeking were very good. They included a 4 ½ star review by John Litweiler in the September 19, 1969 issue of DownBeat (Vol. 36, #19). Litweiler was especially impressed by Bradford’s playing but was concerned that the ensemble’s aural proximity to Ornette’s efforts might ultimately hinder their success.

(There are some that dispute the recording dates between Seeking and Flight of Four. Bradford was sure that Flight of Four was recorded after the Seeking session. Some discographies show Flight of Four being recorded on January 3, 1969, others - including Lord’s Discography - later in April. Bradford was sure it was a later date. The rest of this article is based on the April recording date.)

Bob Thiele and Flying Dutchman

Legendary record producer Bob Thiele had already had a storied career by the late 1960s. He had begun early creating his own Signature Records at the age of 17 to record his jazz heroes. Thiele later made a name for himself producing records for Decca and Coral Records. He was responsible for producing perhaps Louis Armstrong’s biggest hit, “What a Wonderful World.”

In 1961, Thiele took the reins of Impulse! Records from the label’s founder Creed Taylor, who had gone on to head Verve. Thiele brought in one of the recording industry’s most diverse rosters of musicians including John Coltrane, Dizzy Gillespie, Shirley Scott, Yusef Lateef, Albert Ayler and Pharoah Sanders.

|

| Bob Thiele |

It was the “What a Wonderful World” session that would be the catalyst for Thiele’s departure from Impulse!. The producer had run into increasingly stiff resistance from the president of ABC-Paramount Larry Newton. Newton was on Thiele’s case about his choices for Impulse! and his other production work for ABC-Paramount.

Thiele had written “What a Wonderful World” with George David Weiss with the intent of having Tony Bennett record it. Bennett turned the song down. Thiele then offered it to his hero and friend Louis Armstrong. The recording was scheduled for July 1968.

Legend has it that Newton was on hand at the session for a publicity shot with Armstrong. Newton found out that Thiele was planning to have Armstrong record a ballad. He was livid. Newton had wanted to release a more pop oriented number like those that had already been successful for Armstrong. Apparently, Thiele and Newton had it out in the studio and Thiele eventually got Newton locked out of the studio while Armstrong recorded the tune.

Ultimately, the single wasn’t promoted in the United States and sold poorly domestically. The release did extremely well when released overseas, including being the best selling single of 1968 in the United Kingdom.

At this point, Thiele was looking for a way to get out of ABC-Paramount. Thiele established his own production company later in 1968, which was announced in Billboard magazine. He named the company Flying Dutchman Productions after the ghost ship of nautical legend – which was doomed to sail the seas forever. Thiele continued as an independent producer at Impulse! for a while. He managed to license a couple of recordings from Ornette Coleman and record Pharoah Sander’s Karma during this time (Karma’s success eventually got Sanders signed to Impulse!).

Restructuring at ABC-Paramount gave Thiele a perfect opportunity to shove off. The Impulse! offices moved to Los Angeles in January 1969. Thiele remained in New York City.

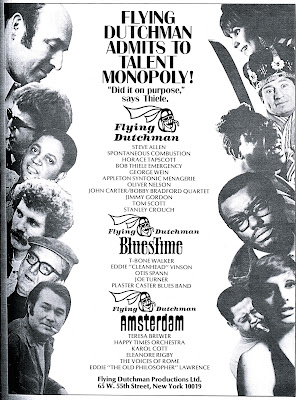

Flying Dutchman Productions finally took flight in April 1969 with funding from Dutch based Philips. Thiele’s production group included three labels: Flying Dutchman, BluesTime and Amsterdam. Thiele also brought a handful of musicians with him, including Louis Armstrong, Johnny Hodges, Gato Barbieri and Oliver Nelson.

Thiele was also on the lookout for new talent and the West Coast was one of his first stops to find it.

Carter and Bradford Meet Thiele

The “What’s Happenin” section of Jazz & Pop for April/May 1969 (Vol. 8, #4/5) announced Thiele’s intentions:

Flying Dutchman Soars

Flying Dutchman Productions, Ltd., headed by Bob Thiele, has signed the John Carter-Bobby Bradford Quartet and pianist Horace Tapscott to the new Flying Dutchman label. Thiele, long noted for discovering new talent, signed and recorded the aforementioned West Coast jazz artists in April. Thiele has started a new blues label for FD, called Blues Time. Already signed are Joe Turner, T-Bone Walker, Otis Spann and Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson. Watch these pages for further adventures of the Flying Dutchman!

Interestingly, the same issue of Jazz & Pop had Carter # 10 for clarinet and Bradford # 8 for trumpet in their Reader’s Poll. No doubt due to their release of Seeking a short time prior to publication.

In the spring of 1969, Thiele went to Los Angeles on a search for West Coast talent. The producer had already begun putting together his initial slew of releases, which would include a collaboration between Oliver Nelson and Steve Nelson (Soulful Brass, FDS 101), the jazz rock super group Spontaneous Combustion (Come and Stick Your Head In, FDS 102) and electro-acoustic composer Jon Appleton’s first album (Appleton Syntonic Menagerie, FDS 103).

In the spring of 1969, Thiele went to Los Angeles on a search for West Coast talent. The producer had already begun putting together his initial slew of releases, which would include a collaboration between Oliver Nelson and Steve Nelson (Soulful Brass, FDS 101), the jazz rock super group Spontaneous Combustion (Come and Stick Your Head In, FDS 102) and electro-acoustic composer Jon Appleton’s first album (Appleton Syntonic Menagerie, FDS 103).

Another interesting release that Thiele had produced was a spoken word record by the Los Angeles based drummer cum poet cum critic Stanley Crouch called Ain’t No Ambulances for No Niggas Tonight (FDS 105). Crouch was originally from California and had been involved as a critic and occasional drummer for some of Los Angeles’s progressive jazz scene. (I reached out to Crouch to talk about his possible involvement in furthering Thiele’s interest in the West Coast musicians. He asked me to follow up another time.)

Bradford recalled auditioning for Thiele after the recording of Seeking, so presumably in the spring of 1969. The audition might have been at the behest of Crouch, who would have been involved in the Los Angeles music scene at the time. While with Thiele, Carter and Bradford recommended that the producer look into recording pianist Horace Tapscott and saxophonist Black Arthur Blythe.

Some discographies have shown that Flight of Four (FDS 108), the first recording that Carter and Bradford did for Thiele, was recorded on January 3, 1969. This would be before the recording session for Seeking. It would be unlikely that this happened as Thiele would have just barely have had Flying Dutchman together as a production company at that point. The date was probably given as 1969, the discographers adding January later on.

Furthermore, the recording session for Horace Tapscott’s The Giant Is Awakened (FDS-107) was held on April 3, 1969 and the release was before Flight of Four. The Jazz & Pop notice mentioned that both Flight of Four and The Giant Is Awakened were recorded in April, therefore the April 1, 1969 recording date for Flight of Four has been the most likely date. The fact that Bradford and Carter recommended Tapscott for a session probably meant that the recordings were made closely together on one West Coast trip for Thiele.

Tapscott went on to say in his autobiography Songs of the Unsung that Thiele was pushed by Crouch and Carter to record his group. Bradford has maintained that Thiele was extremely independent and wasn’t forced to do anything, rather he was very interested in discovering new talent in and around Los Angeles. Tapscott mentioned that he was very impressed that Thiele came to the ghetto to meet with him, though he was wary of what the producer might do with his music. Ulimately, Tapscott left it up to a vote of the band members whether they should record, they voted “yes.”

From the June 26, 1969 issue of DownBeat (Vol. 36, #13):

Meanwhile, other local avant-gardists are having some luck in getting their music recorded. The New Art Jazz Ensemble, co-led by John Carter, reeds, and Bobby Bradford, trumpet (Other members are Tom Williamson, bass, and Bruz Freeman, drums), have recorded for Revelation records and are about to wax for Bob Thiele’s Flying Dutchman label, which has also signed another avant-garde Los Angeles combo, the Horace Tapscott Quartet.

Bob Thiele Emergency

To announce the first slew of recordings for Flying Dutchman, Thiele put together a compilation featuring contributions from most of the artists that were to have releases in the first eight releases of the label. Released under the name Bob Thiele Emergency, the double LP Head Start (FDS-104) was the introduction of the Flying Dutchman record label to the world.

Like his earlier attempt Light My Fire (Impulse!, AS-9159), Thiele tried to provide a mixture of all the musical styles that he was involved and influenced by into one recording. Head Start featured a hodgepodge of groupings and styles blended together into long tracks meant to tell the story of jazz or overt political statements.

Like his earlier attempt Light My Fire (Impulse!, AS-9159), Thiele tried to provide a mixture of all the musical styles that he was involved and influenced by into one recording. Head Start featured a hodgepodge of groupings and styles blended together into long tracks meant to tell the story of jazz or overt political statements.

Head Start was also the first release on Flying Dutchman that featured the playing of John Carter and Bobby Bradford. The quartet was tacked into the final movement of a sidelong piece entitled “The Jazz Story.” The piece was a pasting together of different groups playing music in styles representing the inception of jazz to the present - including the blues, swing, bebop and the avant-garde. Representing the avant-garde, the ensemble played the Carter composition “In the Vineyard” after a recorded statement from Ornette Coleman (“there will always be new forms of music”). “In the Vineyard” later became one of the group’s frequently played tunes.

The “In the Vineyard / Avant Garde” concluded the horns fade out while Horace Tapscott can be heard taking over on the piano.

Bradford: “It was a spliced together event.”

He meant that the quartet was never in the studio with Tapscott and that the pianist’s playing was overdubbed onto a track (an outtake) recorded at the Flight of Four session. It sounded as if the trumpet and clarinet tracks were taken out of the mix and Tapscott played along with the rhythm section until the conclusion of the track. The music broke momentarily before the pianist started up on a different tune in a trio.

A large supplement to the July 1969 issue of Jazz & Pop magazine (Vol. 8, No. 7) heralded the emergence of the new label. It featured a long article on the Head Start album, which included a short quote from Thiele:

For the last (“In the Vineyard / Avant Garde”), according to Thiele, ‘we used Horace Tapscott on piano, and the John Carter-Bobby Bradford group – great musicians from the Watts area who exemplify the music of today.’

Flight of Four

On April 1, 1969, the members of NAJE recorded the material that would be released on Flight of Four (FDS 108). The session was engineered by Eddie Brackett, who had recorded hits by the Ventures, the Cricketts and Dean Martin. Bob Thiele had recently used Brackett as an engineer on a handful of jazz releases for Impulse!, including sessions for saxophonist Tom Scott and guitarist Mel Brown. Brackett would also record Horace Tapscott’s The Giant Is Awakened two days after this session.

The liner notes for Flight of Four did not provide info on the studio the album was recorded but Brackett had been working predominately at United Western Recorders in Hollywood. The studio complex at 6050 & 6000 West Sunset Boulevard was one of the most popular in Hollywood, having been used by artists like Frank Sinatra and the Beach Boys. The 6050 West Sunset address was originally called United Recorders and the 6000 address Western Studios. They are now Ocean Way Recording Hollywood and EastWest Studios, respectively.

The Carter / Bradford session most likely took place in the B Room at the United Recorders building at 6050 West Sunset.

The ensemble recorded mostly Carter original tunes, with one exception - “Woman” by Bradford.

Bradford: “John was a prolific writer. He wrote every day, so he always had a lot of stuff. I always waited for the Lord to give me inspiration. I didn’t sit around with a green visor and a sharpened pencil.”

No information was found that listed the order the material was recorded.

The first track to appear on the LP was Carter’s “Call to the Festival,” introduced by Freeman’s martial drums and Williamson’s rumbling bass before the winds present the intricate, linear melody. The ensemble typically avoided a counting off tempo, instead they’d maintain eye contact to initiate the tune and segue into solos and further development. The tune provided a space for the ensemble to explore varying tempos, dynamic ranges and moods, while maintaining a strong since of melodic direction. The conclusion was especially strong.

|

| Eddie Brackett |

There was an obvious indebtedness to the philosophy of Coleman, including similar musical concepts and instrumentation. Carter played alto on “Call,” which was Coleman’s primary instrument. There were obvious melodic devices used similarly to Coleman’s, including the “crying” sound that Coleman used so frequently in solos and in composing.

Another Carter composition “The Second Set” had a shorter melodic theme and higher tempo, which launched quickly into solos. Carter took the first on alto, showing his fleet fingered forays and passionate overblowing to dramatic effect. Williamson’s bass playing was especially strong in the trio segment, extremely forceful and demanding. Bradford’s trumpet solo provided many interesting thematic ideas but he eventually settles on a repetitive figure of descending notes for a number of choruses. Overall, the texture remained staid as the ensemble had strong forward motion throughout, breaking only for a powerful Freeman drum solo.

|

| Freeman |

Carter’s “Abstractions for Three Lovers” had an interesting melodic concept with a solo melodic theme where the bass began a repetitive two note pattern until the horns layer on top to follow an upward melodic line. The music slowed for a segment where Carter’s alto and Bradford’s trumpet mirror a theme before reverting to the repeating two notes, which build and drop.

|

| Williamson |

Finally, Carter’s “Domino” finished the disc with an uptempo and more swinging piece. The melody was once again very intricate with the horns playing in unison with sudden flourishes of 16th notes. The piece featured Carter on tenor sax, obviously not his standard horn choice as his solo features a number of squeaks. Overall, Carter’s performance was very good, his solo provided a wide range of ideas that led him over the full range of the horn. Bradford framed the melody during his solo finding new articulations and arpeggiations – building his solo thematically.

Prior to release, Thiele advised Carter and Bradford to rethink the name of the ensemble. Up until this time, the quartet had been called the New Art Jazz Ensemble but the producer thought it best for promotion that the group should go under one or both of the horn players’ names. Both Carter and Bradford voiced an issue with the idea as they didn’t want to slight Freeman or Williamson but eventually acquiesced to Thiele. Thus, Flight of Four was released as the work of the John Carter & Bobby Bradford Quartet.

The recording was re-mixed and mastered by Tony May in New York City. He was a well-respected engineer who had done mixing work for many Verve releases, continued work with Flying Dutchman and became the go to US engineer for ECM. May also worked classic recordings by rock and folk groups like the Band, Blue Cheer and Van Morrison to name a few.

The recording was re-mixed and mastered by Tony May in New York City. He was a well-respected engineer who had done mixing work for many Verve releases, continued work with Flying Dutchman and became the go to US engineer for ECM. May also worked classic recordings by rock and folk groups like the Band, Blue Cheer and Van Morrison to name a few.

The packaging of the album was the lovely Flying Dutchman gatefold with design by Robert and Barbara Flynn of Viceroy design agency. Radical writer/jazz critic Frank Kofsky was recruited to write the liner notes. He called out the “provincialism” of the jazz world, one that subjugated the rest of the world’s creative offering not originating in the jazz capital of New York City. The notes don’t go far in describing the musicians or the music.

There were also some nice portraits of the musicians by Irv Glasser. Glasser's cover photograph has the quartet in front of a bronze sculpture by the Romanian-born, Canadian artist Sorel Etrog entitled Moses (1963) at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. (The sculpture is currently in storage at LACMA). The photographs in the gatefold are from the recording session.

The original release date couldn’t be ascertained but the first review showed up in the November 27, 1969 issue of DownBeat (Vol. 36, #24). Most likely, the release was around the same time. The review was a fairly good one written by the then assistant editor Lawrence Kart, who gave the recording 4 out of a possible 5 stars. Two months earlier, John Litweiler had given the group’s Seeking a four and a half star review in the same publication (September 18 – Vol. 36, #19).

There were also some nice portraits of the musicians by Irv Glasser. Glasser's cover photograph has the quartet in front of a bronze sculpture by the Romanian-born, Canadian artist Sorel Etrog entitled Moses (1963) at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. (The sculpture is currently in storage at LACMA). The photographs in the gatefold are from the recording session.

The original release date couldn’t be ascertained but the first review showed up in the November 27, 1969 issue of DownBeat (Vol. 36, #24). Most likely, the release was around the same time. The review was a fairly good one written by the then assistant editor Lawrence Kart, who gave the recording 4 out of a possible 5 stars. Two months earlier, John Litweiler had given the group’s Seeking a four and a half star review in the same publication (September 18 – Vol. 36, #19).

Kart enjoyed Flight of Four more than the earlier effort because “the group sounds more relaxed and the recording is less dry.” The critic remarked on the leaders’ obvious influence from the Ornette Coleman school:

Imagine Coleman or Bradford listening to Charlie Parker in 1949. As devoted boppers, they memorized and elaborated on what they heard, like thousands of other young musicians. But, surrounded by the Southwestern blues conception that gave birth to Parker and Lester Young, their elaborations were subject to feedback from the initial source. Thus, through a unique conjunction in time and place, a genius like Coleman could make relations between the free, expressionistic use of melody and rhythm in Southwestern blues and similar qualities in Parker’s highly sophisticated music, ending up with seemingly radical innovations (they were radical in effect, but the method was pretty much one of intuitively combing already existing things).

In such an environment, talented musicians like Bradford and Carter could emulate their idols (Fats Navarro and James Moody, I would guess) and, as they matured, extend their initial inspirations into novel areas. And feedback enters once again when Carter and Bradford were influenced in the ‘60s by Coleman’s fully developed music.

The result is that this group sounds quite fresh and new; not because they are using new musical materials, but because, like Coleman, they legitimately tap jazz roots and bring forth new relations between familiar things.

Kart went further to say that he really enjoyed Bradford’s playing, finding his melodic concept “reminiscent of Buck Clayton.” He wasn’t as impressed with Carter’s solo playing, however. Though he did say that Carter’s music was “honest music - free from the affected hysteria which sometimes plagues the avant garde.”

The next bit of press that Carter and Bradford received was in the January 1970 issue of Jazz & Pop (Vol. 9, #1). The duo had a long interview with Frank Kofsky that was accompanied by a number of Irv Glasser photographs taken at the Flight of Four session. The interview settled on issues pertinent to the creation and promotion of their music in Los Angeles. The recording wasn’t mentioned at all. (Some of the information regarding performing opportunities was mentioned earlier in this article.)

The review of Flight of Four in Jazz & Pop didn’t show up until the March 1970 issue (Vol. 9, #3). Critic Will Smith enjoyed the record but didn’t find it groundbreaking.

The group’s sound is close to that of the early Ornette Coleman unit with Cherry, Haden and Blackwell – Carter’s tunes (he composed all the lines except Bradford’s “Woman”) are like early Coleman works and the loose unison ensemble edge is similar.

Once again, Bradford’s playing was a standout for Smith. He compared the trumpeter to Don Cherry – “they both use fast, spinning little phrases to punctuate and space their lines” – but thought that Bradford’s sound was most similar to that of Ted Curson.

Smith didn’t think that Carter felt comfortable in the free playing and heard echoes of James Moody along with the obvious Coleman references in his sound.

Bradford said that the recording continued to get good responses from critics around the world but it didn’t benefit the group financially. Gigs were still hard to come by in Los Angeles and the group made very little effort to tour outside, even when prodded to do so by Thiele.

The Flying Dutchman producer maintained that the only way the record would be successful was if the group would move to New York. The musicians were not about to leave Los Angeles even if it meant increased success as recording and performing artists, they were already too invested in their lives out West.

Though the group didn’t follow Thiele’s suggestion, the producer did go record a follow up Flight of Four with a second recording.

Self Determination Music

In the August 1970 issue of Jazz & Pop (Vol. 9, #8), critic John Sinclair wrote a very long and involved multiple record review under the title “Self-Determination Music.” Among the reviews, were short descriptions of two Flying Dutchman recordings, Horace Tapscott’s The Giant Is Awakened and Stanley Crouch’s Ain’t No Ambulances for No Nigguhs Tonight. Whether the article’s title was influenced by or was the influence for the title of Carter and Bradford’s subsequent release has remained a mystery.

In the August 1970 issue of Jazz & Pop (Vol. 9, #8), critic John Sinclair wrote a very long and involved multiple record review under the title “Self-Determination Music.” Among the reviews, were short descriptions of two Flying Dutchman recordings, Horace Tapscott’s The Giant Is Awakened and Stanley Crouch’s Ain’t No Ambulances for No Nigguhs Tonight. Whether the article’s title was influenced by or was the influence for the title of Carter and Bradford’s subsequent release has remained a mystery. Carter and Bradford took the quartet plus the additional (uncredited) bassist Henry Franklin – who would later record a number of now classic recordings on Black Jazz and Catalyst - to TTG Studios to record their third disc as a group around the same time as the article. Bradford was sure that it was the summer of 1970.

|

| Shooting Star formerly TTG Studios |

No recording date could be found for this session, nor could the recording order the ensemble took could be established.

The first composition on the album was Carter’s “The Sunday Afternoon Jazz Blues Society.” Later, the tune would show up on the album Comin’ On (hat ART 6016, 1989) as “Sunday Afternoon Jazz Society Blues,” alluding to a possible mistake made by the Flying Dutchman layout designers.

The piece began with the two bassists and drummer playing freely before the unison ascending melody shared between alto sax and trumpet came in. The melody was very reminiscent of Coleman’s mix of fluid lines with an almost taunting countermelody.

Carter took the first solo that was very blues influenced as he reached for altissimo notes that would later become his stock in trade. Bradford emerged as Carter’s solo ended. The trumpeter played with the time within the tempo of the song, he cuts it in half only to speed up once more. The piece was a showcase for the expanded rhythm section as they really keep up an impressive amount of energy throughout the piece.

|

| Carter |

Bradford’s lone composition on the LP was “The Eye of the Storm.” Williamson led in with the solo bass melody while Freeman created atmospheric washes of cymbal. The piece began to pick up pace as the trumpet melody emerged, accentuated by the alto. The true impact of the melody would be heard as the horns interlock and then break apart. The swirling rhythm section made a tremendous bed of activity for the horn players to solo over.

“Eye of the Storm” was the longest piece the group had recorded up until then. The rhythm section remained aggressive while the soloists would play with the melody and improvise, building or diminishing the tension by playing off each other, laying out, slowing or quickening pace. The group interplay was probably best displayed on this piece as the texture could switch from subtle tension to full aggression. The energy was unrelenting, even the breakdown with the duo basses soloing kept up the vigorous energy. The energy only subsided after the ensemble died away leaving only Williamson’s bass and Freeman’s lingering cymbal washes.

The b-side began with Carter’s “Loneliness,” a slow, melancholy ballad introduced by bowed bass, subdued trumpet and Carter’s flute along with Freeman on bells. The lush mood would be interrupted by Carter’s strident alto underlined by Bradford’s muted trumpet echoing the call. The meditative quality of the track was furthered by the reliance of Carter on the flute to accompany while he switches to alto for all solo flights.

The recording of “Loneliness” was especially warm, as the horns’ inflections and the bass tone really stand out. The group established its own sound world that would eventually be echoed by many spiritual jazz ensembles during the later part of the 1970s.

|

| Bradford |

The bass set off quite a clip for Carter’s “Encounter.” The horns are found locked into the unison melody after a segment that featured a wide round with the alto following the trumpet. The rhythm section set up a tremendous rumbling that barreled through the piece. Bradford’s dexterity was on full show as he climbed higher and higher in register through his solo. His clear tone was worth noting even while he experimented with swaths and smears of sound.

Carter was featured on tenor once again on the closer. His technique seemed more keyed in on this performance, which allowed him to try some extreme yet controlled effects on the horn – honks, squeals and altissimo range. The solo section featured the extremes of the two horn players’ ranges. The unrelenting force from the bassists and drummer was tremendous and once again the dual bass segment was extremely expressive. Freeman took one of the best solos of either recording - searing and snare heavy - before an extended head section back out.

The packaging for Self Determination Music was designed by Lou Queralt, who went on to do a couple other Flying Dutchman packages including Gil Scott-Heron’s Small Talk at 125th and Lenox. The cover photo of what appeared to be a tepid pool of water or possibly the La Brea Tar Pits was taken by Elihu Blotnick.

The packaging for Self Determination Music was designed by Lou Queralt, who went on to do a couple other Flying Dutchman packages including Gil Scott-Heron’s Small Talk at 125th and Lenox. The cover photo of what appeared to be a tepid pool of water or possibly the La Brea Tar Pits was taken by Elihu Blotnick.

Regular Jazz & Pop contributor Robert Levin provided the liner notes. The themes of the notes were the gradual acceptance of the new music that Ornette Coleman unleashed upon an unprepared audience and how these new forms of expression meant “the black-American’s liberation from four-hundred years of uncertainty regarding the worthiness of his identity.” These musicians had found a way to “liberate” themselves from prevailing forms. While supportive of the efforts of the generation’s attempts at shedding the shackles of the conservative musical society at large, the notes haven’t provided much information about the ensemble and what they were trying to achieve themselves.

The album was most likely released in the early fall of 1970. The first review of the album was found in the October 28, 1970 issue of DownBeat (Vol. 38, #18). Critic John Litweiler gave the recording 4 out of 5 stars. Litweiler was especially taken by Carter’s writing: “Carter’s themes on Sunday and Encounter are long, single lines very much broken and contrasted. They are like certain pieces Ornette Coleman and Anthony Braxton used to write (hear that Ornette phrase in Sunday), but the phrases are more brittle and Carter’s wit is more electric.” He also found that Carter’s playing had strengthened since the previous release.

Litweiler maintained that the recording didn’t showcase Bradford’s best playing but thought that “Loneliness” provided the best glimpse at the trumpeter’s ability. He also remarked on how much he enjoyed Freeman’s drumming but thought that the recording would have been more effective with a single bassist.

Self-Determination Music is an LP well worth your attention, though perhaps not as successful as Flight for Four or Seeking (as the New Jazz Art Ensemble). These players have staked out an important place within the mainstream of jazz; their care and skill and love for their art communicate intensely. And considering Carter’s development as a composer and Bradford’s fresh trumpet challenges, the promise of future discoveries is bright indeed.

Another review could be found in the March 7, 1971 issue of the New York Times. Critic Clayton Riley reviewed Self Determination Music and vocalist Leon Thomas’s first recording for Flying Dutchman. Riley likened the ensemble’s work to that of Charlie Parker’s – geniuses baffling audiences with new, unexpected forms.

I refer to Parker’s logical descendants because I think the intentions involved in his music and theirs are precisely the same: the destruction of “normality,” the creative assassination of cultural and artistic caretaking establishments.

Riley was most impressed by the take on “Loneliness,” likening Bradford’s playing to Miles Davis’s. He referred to the energy of “Encounter” as ‘street combustion.’

More ‘70s vernacular:

These Brothers are not formula followers; their work neither begins nor does it end in any sense that we might call formal or traditional or … whatever. Their playing is forceful and free. And it is astute also, the men know – I wanta thank ya – know their instruments and use them in an informed as well as a daring fashion.

From there, Clayton talked about the ability of Black music to be simultaneously beautiful and violent, citing Louis Armstrong, Art Tatum, Lester Young, Art Blakey, Ornette Coleman and Sun Ra as examples.

The Carter-Bradford Quartet will, I hope, keep on gittin’ up. This is their second album, I understand, and what they’ve done with it is show us what can and will be in contemporary music’s new and near future. Check them out.

The Times review had obvious mistakes – omission of the second bassist and limited knowledge on of the ensemble – but it was very positive to be received so well in such an important publication.

Aftermath

Though there had been a bit of good press, the records never really took off. Both Carter and Bradford remained in Los Angeles working as educators. Bradford started off at CalArts and then moved to Pomona College, where he remained for over 25 years.

The pair didn’t record or perform as frequently after Self Determination Music. It wasn’t until 1972 that their second release on Revelation came out.

Secrets (REV-18) featured only a single track from what formerly was the New Arts Jazz Ensemble. “Circle” was recorded at the Herrick Lounge at Occidental College on November 9, 1971. The three studio tracks were recorded on April 4, 1972 and featured bassist Louis Spears, drummer Ndugu Chancler and pianist Nate Morgan.

Secrets (REV-18) featured only a single track from what formerly was the New Arts Jazz Ensemble. “Circle” was recorded at the Herrick Lounge at Occidental College on November 9, 1971. The three studio tracks were recorded on April 4, 1972 and featured bassist Louis Spears, drummer Ndugu Chancler and pianist Nate Morgan. From there the duo diverged as they became more involved in their day-to-day lives. Bradford would go on to finally appear on an album of Ornette Coleman, Science Fiction (Columbia KC 31061, 1972). Before the Secrets session, the trumpeter also ventured to Europe and recorded with members of John Steven’s Spontaneous Music Ensemble. He later returned to the United Kingdom and recorded Love’s Dream with Stevens, saxophonist Trevor Watts and bassist Kent Carter at the end of 1973.

It was about that time that Carter shifted his attention predominantly toward the clarinet.

Bradford: “I was not making happy noises about him leaving the alto. I loved his saxophone playing.”

Carter showed up as a collaborator on a few releases during the 1970s, including Vinny Golia’s Spirits In Fellowship (Nine Winds 0101, 1977), Tim Berne’s The Five-Year Plan (Empire Productions EPC 24K, 1979) and James Newton’s The Mystery School (India Navigation IN 1046, 1980). He released two recordings as a leader during this time, a live album, on a small label, called Echoes From Rudolph’s (Ibedon IAS 1000, 1977) and a recording of a suite of folk tunes called appropriately enough A Suite of Early American Folk Pieces for Solo-Clarinet (Moers 02014, 1979).

Bradford and Carter would resume their partnership on subsequent recordings of Carter’s Quintet and Octet. While Bradford still enjoyed playing standard jazz repertoire along with his own material, Carter really focused on his own compositions, creating a series of five recordings in a suite that would become his legacy as a writer and conceptualist – Roots and Folklore: Episodes in the Development of American Folk Music (Dauwhe (Black Saint BSR 0057, 1982), Castles of Ghana (Gramavision 18-8603-1, 1986), Dance of the Love Ghosts (Gramavision 18-8704-1, 1987), Fields (Gramavision 18-8809-1, 1988) and Shadows on a Wall (Gramavision R1 79422, 1989)). (Hopefully, these tremendous releases will be reissued at some point.)

Carter’s legacy has remained a vital part of the story of creative music in the United States. He was a gifted performer, educator and conceptualist. Carter passed away on March 31, 1991 in Inglewood, California.

Bradford’s legacy has continued to grow as he has continued to be an important voice in the contemporary world of jazz and improvisation. He has continued his roll as an educator, predominantly at Pomona College. Bradford has also been an in demand sideman and leader, recording with musicians as diverse as Nels Cline, Frode Gjerstad and David Murray.

***

As of December 31, 2011, the Flying Dutchman catalog had reverted back to the Thiele Estate. The catalog had been previously controlled by Sony/BMG. Any documents would presumably be with Thiele’s family. (I did send a message to Bob Thiele’s son to see if any info might be readily accessible with no response.)

There has been word that International Phono has planned to release reissues of these two recordings in the fall of 2012 or spring of 2013.

I would like to sincerely thank Bobby Bradford for sharing his time and information. I would also like to thank the staff at the Institute of Jazz Studies at Rutgers University and the expedient staff of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art's Research Library. Also, thanks to Charles Sharp and Clifford Allen for the tips.

I would like to sincerely thank Bobby Bradford for sharing his time and information. I would also like to thank the staff at the Institute of Jazz Studies at Rutgers University and the expedient staff of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art's Research Library. Also, thanks to Charles Sharp and Clifford Allen for the tips.

Wow, fantastic article. John Carter still deserves wider recognition, but I guess he'll be rediscovered one of these days.

ReplyDeleteThanks

Thank you for your work in this really fine essay. Brandford and Carter ' s music is really Worth such a study. You have been greatly appriciated.

ReplyDeletesuperb scholarship. well done!

ReplyDelete#" Self Storage "also one of the out standing SELF storage Copany in Uk ,

ReplyDeleteCheapness with best quality is the reason are that every person most prefer to get their services ...

# For more detail click here