BYOV took an unintended vacation for about two months. I hope that you weren’t worried.

Absence made some folks’ hearts grow fonder… I was very happy to see a fairly large crew with whetted appetites for music and extended ad nauseum discussion. Yippee!

BYOV #11 convened once again at Barbès in Brooklyn on June 3rd with a very nice turnout, including a new demographic which I’ve been trying to target for a while – young women. On suggestion of BYOV attendees, of course.

I happened to think that this series of themes was especially challenging. Though, they didn’t seem to faze my pro music selectors. Well, maybe a bit.

Here were the themes:

a) Instant classic. What are some tunes from the 2000s you think deserve to become standards or that are likely to be considered "classic" songs in the future? "Sexy and I Know It," anyone?

b) Giant (mis)steps. Oh how we love talking about misadventures and poor choices by musicians. Bring in your best example.

c) Out of left field. It is easy to become engrossed in a certain musical avenue. Every so often, a song or musician from a completely different place will hit you. What song do you love that came from outside your comfort zone?

What would you have picked?

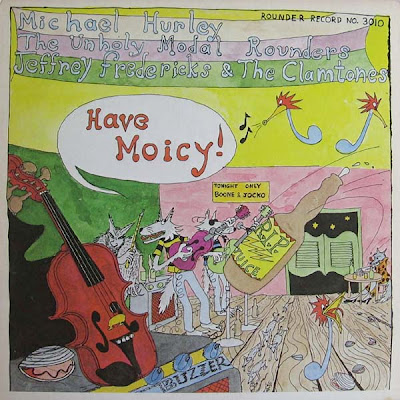

1. Michael Hurley / The Unholy Modal Rounders / Jeffrey Fredericks & The Clamtones – “Hoodoo Bash” from Have Moicy (Rounder 3010, 1976)

Presented by Seton Hawkins – LP – Theme: C

Seton brought us a recording that he felt was originally out of his comfort zone but that he grew to be “kind of in love with.”

Steve: “What exactly is your comfort zone?”

Seton: “I guess classical and jazz and anything out of Africa. Oh yeah… And Elvis – mainly early Elvis.”

We listened to a cracked country/folk tune featuring fiddle, bass, guitar and brushed drums. Oh… and some odd warbled vocals.

Seton mentioned that this album was a “collaboration” between three acts, the acts also happened to be quite incestuous.

Richard (who happened to know the album off the bat): “Have you seen the documentary?”

Seton: “Hell yes!”

Jason: “Sounds like the Holy Modal Rounders.” Very, very close.

So… This ensemble and the subsequent recording provided a very complicated scenario. Want to hear it? Here it goes…

The Holy Modal Rounders was a folk ensemble from New York City created by Peter Stampfel and Steve Weber in the early 1960s. The two musicians were introduced to each other by Antonia Duren, who went on to write many songs for the Rounders (including “Hoodoo Bash”).

Separately and later in the 1960s, songwriter Jeffrey Frederick put together a group that became known as the Clamtones in his native Vermont. He also began collaborating with songwriter/multi-instrumentalist Michael Hurley shortly thereafter.

Frederick moved to Portland, Oregon in 1975. It just so happened that Steve Weber of the Holy Modal Rounders had relocated there as well. The two leaders shared a backing band known as The Clamtones under Frederick and the Holy Modal Rounders while performing with Weber.

Peter Stampfel hadn’t made the move to Portland and ended his collaboration with Weber. So, when he met up with Frederick/Hurley and Co. on a road trip, he decided to join in - leading this loose group of folk musicians under the guise of the Unholy Modal Rounders.

On this tour, the collective recorded Have Moicy!. Making the situation even more confusing, the credits provided for the album have the ensembles completely jumbled.

“Hoodoo Bash” was written by Antonia Duren and featured Peter Stampfel on vocals, Robert “Frog” Nickson on drums, Paul Presti on guitar and Robin Remaily on mandolin. The album notes credited Jeffrey Frederick and Jill Gross on vocals.

There were further reasons Seton enjoyed the record, most importantly: “Michael Hurley sounding like Jimmy Buffett – if Jimmy Buffett didn’t suck.”

Funny that this was presented first as we had just been marveling over Jason’s new oral history of the ESP label – the label that originally released the Holy Modal Rounders albums.

2. Lionel Hampton – “California Dreamin” from Them Changes (Brunswick BL-754182, 1972)

Presented by Ben Monder – CD – Theme: B

Ben: “So I first heard this on WFMU’s Incorrect Music radio show. I knew that I had to get it after I heard it. It was definitely out of my comfort zone.”

We heard a funky track with a languid yet soulful vocalist singing the very familiar “California Dreamin’” by the Mamas and the Papas. Bass heavy, tight snare and a horn section beefed the track up.

Richard: “It isn’t Bobby Womack is it?”

Zak: “No. If it were Bobby, this would be a classic.”

Richard: “You call this a misstep?”

“Great bass player. Do you know who it is?” No. (Turned out to be a bassist by the name of Steve Rushin.)

Steve: “Is it a known artist?” Oh yeah – The last part will give it away.

Then the vibraphone came in. Huh?

The singer: “Help me somebody!”

Steve: “True words…”

“Is the vocalist a different person than the vibraphonist?” I don’t think so. I think it is the same guy.

The vocalist’s style was reminiscent of James Brown but additional vibes talent didn’t line up.

Steve: “Were the brass players in his band?” Yes.

Steve: “Lionel Hampton. But I don’t think he was singing.”

It was indeed the Lionel Hampton band from a 1972 recording called Them Changes. The record featured a number of soul and rock covers done by a slick large ensemble and vocalists. The vocal on this track was sung by forgotten soul singer Lee Moses. (Here is a link to his only album as a leader.)

Steve was positive that Lionel wasn’t the vocalist as he had sung on recordings in the past. So we listened to Hampton’s rendition of “One Sweet Letter From You” recorded in 1939.

Steve: “He’s no James Brown…”

“Oh c’mon… Just skip ahead to the part where he starts shrieking.”

3. Jacob Garchik – “The Heavens” from The Heavens: The Atheist Gospel Trombone Album (Self Released, 2012)

Miles: “I guess this is out of my comfort zone. I think it is interesting and wanted to play it. But if I saw it in a store, it probably wouldn’t have been something I would have picked up at first glance.”

The listeners were greeted by a warm trombone led brass ensemble playing a bluesy, gospel arrangement.

“How old is this?”

Miles: “This is very, very new.”

Ben: “Is it Jacob Garchik? His new thing where he plays all the instruments?” Yep.

The San Francisco born, New York based Garchik has been performing regularly in a variety of ensembles – from jazz and improvised music to the brass heavy Mexican Banda - in the local NYC and global creative music scenes for some time.

Miles: “Technically this is really amazing. And it is very soulful. The rest of the record is just as good. There’s a bit of klezmer, gospel, blues…”

Garchik wrote and played all the parts on this recording - overdubbing parts to make a brass choir. A really, lush beautiful recording.

I’d like to thank Jacob for sending a copy of the disc and allowing me to stream the track for the blog. The CD will be released on July 31. Watch this site for more details: JacobGarchik.com.

4. Quintetto Vocale Italiano performing Carlo Gesualdo – “Asciugale I begli occhi, W5.57” from Sämtliche fünfstimmigen Madrigale (Telefuken, 1965-1969)

Presented by Thomas Heberer – LP – Theme: C

Thomas presaged playing his selection telling us that he had a “broad comfort zone.”

Thomas: “My musical world began with jazz and then began opening up. Sometimes I run across a record that I’m not comfortable with but that usually just opens new doors.”

Thomas was particularly taken with this selection that he wouldn’t have otherwise discovered without taking a chance.

We heard a vocal group of five voices performing a restrained, somber piece. The parts moved slowly and had a wide range of harmonic coloring shared between the parts.

“I can’t tell what language it is in.” Italian.

Ben: “Is it Gesualdo?” Yep.

Carlo Gesualdo was a very special composer for his time and he also had quite an intriguing story. He was the Count of Napoli at the end of the 16th century, late in the Renaissance period. Being a very wealthy man, Gesualdo was able to afford his own orchestra that played his compositions but not outside of his estate. He composed for his own enjoyment.

Gesualdo’s music was unique to the period. He used chromatic methods that wouldn’t be heard again for 200 years and wrote compositions to express emotional conditions, not in celebration of God.

The emotional conditions Gesualdo faced were extraordinary. In 1580, he caught his wife Donna Maria d’Avalos in bed with her lover Fabrizio Carafa. Gesualdo murdered them on the spot and displayed their bodies in front of the palace. He was not prosecuted because of his royal status.

Apparently, there was a shift in Gesualdo’s compositional style following the murders. He began feeling guilt for what he had done. Thus opened a new compositional chapter, one of a depressed count – his music becoming more somber and affected.

Thomas: “His music is an island. It was very extreme for the time period. And since no one listened to it, the music was very isolated. So no one cared about it for 200 years.”

Gesualdo wrote six books of madrigals. Three books came before the murders, three after. This particular madrigal came form the fifth book and features remarkable use of chromaticism and counterpoint.

Thomas: “He was a conscious destroyer of rules.”

I tried to find the exact recording that Thomas provided but could not. This recording was done by Claudio Cavina and La Venexiana on a disc entitled Gesualdo: Quinto Libro de Madrigali (1611).

5. John Coltrane – “My Favorite Things” from My Favorite Things (Atlantic SD 1361, 1961)

Presented by Steve Futterman – MP3 – Theme: B

Our favorite agent provocateur was next.

The familiar sound of Coltrane’s soprano debut floated out of the speakers as everyone looked around the room. We could all see where this was going.

The familiar sound of Coltrane’s soprano debut floated out of the speakers as everyone looked around the room. We could all see where this was going.

Steve: “How did the soprano saxophone destroy jazz?”

Richard: “I think the Stratocaster has done way more damage.”

There were more than a couple of guffaws. But Steve asked his question in earnest.

Oran: “Well… Isn’t it Sidney Bechet’s fault?”

Steve: “But clarinet was his first instrument. He doubled on soprano.”

Steve wanted to clarify that he wasn’t slighting Coltrane’s work or Steve Lacy’s exceptional focus on the horn but took issue with tenor players doubling and/or focusing on the soprano.

I suggested that the fact that the instrument was in the same key (Bb) as the tenor and had the same fingering made it easy to transfer to. Though, the fact that a player may have a great sound on a tenor doesn’t ensure he would have a good or even mediocre sound on the soprano. Honing a tenor embouchure versus a soprano embouchure would take real work on the part of the musician.

Richard tried a more musical approach to reason why players might choose the soprano: “The soprano is strident and cuts through anything. Plus it has a call to prayer kind of sound.”

Steve stuck to his guns. He thought that the “Middle Eastern” inflection that frequently appears with soprano has been overplayed.

He also thought that though Wayne Shorter has spent a long time developing an identity on the soprano, the legendary saxophonist had a more pronounced identity on tenor. The problem was Shorter’s approach to the horns: robust and melodic on tenor while short and motif-based on soprano. That had developed into the common approach for all doublers and eventually the common identity for the soprano.

Love to hear some opinions from folks that favor the lighter horn…

6. Miles Davis – “Pharaoh’s Dance” from Bitches Brew (Columbia GP 26, 1970)

Presented by Robert Futterman – CD – Theme: B

Here was another easily recognizable selection. I believe it was Steve’s daughter India who promptly guessed artist correctly.

Robert: “What was I thinking? I really liked this recording when I first bought it. Now I listen and ask: why do I like this? It is aimless. There are all these great musicians here. Where are they going? Why don’t they get there sooner?”

Robert: “What was I thinking? I really liked this recording when I first bought it. Now I listen and ask: why do I like this? It is aimless. There are all these great musicians here. Where are they going? Why don’t they get there sooner?”

It wasn’t that Bitches Brew had fallen out of Robert’s favor but it remained a mystery why this recording has remained a classic in the jazz lexicon.

Zak: “It may have been aimless but it was distinctive. They tapped into something unique.”

Yet the argument would remain that the Bitches Brew sessions were an amalgamation of hours of jamming without a clear purpose or even any real themes. This project might have been more historically relevant because it was more or less a project of studio excesses, i.e. putting together a tremendous ensemble of talent, riffing on hours of tape and finally having a producer (Teo Macero) sculpt a product out of it.

Richard: “You have to consider the time and the historical context.”

Richard maintained that at the time, these long jams were happening all over. Many groups took advantage of the drug culture and subsequent open mindedness of a younger generation of listeners. The Grateful Dead took a similar approach but were much more aimed at building to a specific moment.

Richard: “The Dead presented more free music to a wide range of listeners than any other band.”

Jason: “Was Miles’s music ‘free music’?” Maybe not, but structure was definitely the defining issue here.

Robert: “What bothers me is the lack of structure.”

We discussed how Teo Macero was the real hero for this and many other Miles projects following. Macero ultimately made compositions out of raw musical material. These recordings were essentially musique concrète.

There was also the question of length as many of the compositions on Bitches Brew exceeded the 12-minute mark.

Seton: “What about Wagner? Tristan and Isolde is extremely long but remains a classic.”

Amazing that this recording can still prompt such a heated discussion nearly 50 years after its release. Or maybe it’s just us…? I fear it might be.

7. Kip Hanrahan – “Busses from Heaven” from Beautiful Scars (American Clavé AMCL 1060, 2007)

Presented by Jason Weiss – CD – Theme: A

Jason: “I don’t know if it is a classic but I think it is a good tune.”

Richard: “We’ll be the judges of that…”

The Afro-Cuban song featured a measured clave, violin and English lyrics. I thought the growling spoken words were reminiscent of Bill Laswell’s recordings of Burroughs on his Material Seven Souls recording. The Afro Cuban bit didn’t fit the Laswell persona, however.

“Is this a great performance or a great tune?”

Jason: “Well, considering the artist may or may not actually be playing on this tune, I’m not sure. But I think that the music really stays with you. There is a lot of layering. Many textures.”

No one guessed who the artist was.

It turned out to be Kip Hanrahan. His work has been kind of popular around BYOV for a little while. Richard had previously brought another project that came out on his American Clavé label, Conjure.

There has been some question as to Hanrahan’s involvement in the actual music making. He has always been credited as the producer and/or director of projects that came out on American Clavé but many musicians have disputed his input or activity. Hanrahan has also been a poet, vocalist and percussionist on the side.

Apparently in the live situations, Hanrahan has tended to move about the stage, occasionally playing percussion or whispering direction to players. There has been reason to suspect that he hadn’t recorded on tunes from his own recordings.

While his production style may be a mystery, Hanrahan’s taste has never been suspect. Born of Jewish and Irish decent, he was raised in the Bronx listening to Latin and Black music. This led him to create and produce projects that were very much focused on Afro-Cuban, salsa, tango and jazz. Hanrahan’s legacy might be that he was a great organizer rather than musician or producer.

After Jason’s presentation, we began to discuss what we should be deemed a “modern classic.”

Of course, there were a couple of angles to approach this from. There was the classic popular song. There are hundreds of tunes written every year that are loved for a time and then forgotten. A few get passed down through generations of listeners.

Popular music has proven to be tough to gauge, especially by the crowd that turns up at BYOV. Generally music snobs, the BYOV regulars have found it hard to digest most current popular music. Seton provided an example of a modern songwriter that could be a potential successor of past “classic” progenitors, Stephen Merritt of the Magnetic Fields.

Steve was more interested in the jazz component in generating classic material. His main issue has been that there are no longer composers creating music in the classic jazz cannon – compositions that peers use in their own repertoire, etc.

Steve: “There are no more Horace Silvers…”

We discussed this at length. Most classic jazz compositions were either standard popular material taken from musicals of the day (the American Songbook) or pieces written on the chord changes of these tunes. Occasionally, there came a composer that had an impact by writing tunes that other jazz musicians took on.

The creation of a classic song cannot really be judged until later. It took some time for compositions of composers like Horace Silver, Thelonious Monk and Herbie Hancock to be regularly heard as part of the jazz canon.

Thomas: “We’re not in a period for covering. There have been a few recent examples, like Vijay Iyer’s covering Julius Hemphill, but overall musicians are composing their own material.”

Ben: “Cover tunes are really used to imbue the performer’s own identity, anyway.”

Thomas also mentioned that most current musicians seemed to be looking to establish their own compositional identities rather than look to past forms, though using others’ compositions could provide a frame of reference to the artist’s particular sound and approach.

The past also had other imperatives. Recording was still a money making endeavor for artists and labels. A label like Prestige would have a group come in without any rehearsal time, pick a few tunes and record. The songs they played weren’t new compositions typically but standards that would be familiar to the musicians.

Not completely satisfied with his query results, Steve pointed out that Ornette Coleman was a perfect model of what he was searching for. Coleman has been known as a great melodist with many players being familiar with his tunes.

“A genius like that comes only once a decade or so…”

Only time will tell. (I’m going with all the clichés today, huh?)

The conversation was long, interesting and involved. So much so it was hard to record. Another reason to get your ass to BYOV.

8. Darius Jones – “The Enjoli Moon” from Book of Mae’bul (Another Kind of Sunrise) (AUM Fidelity AUM072, 2012)

Presented by Zak Shelby-Szyzsko – CD – Theme: A

Breaking in to smooth out the situation after our extended debate, Zak wanted to play a recording by a “young guy that fits the Ornette mold.”

Zak: “This tune really sticks in my head. I find myself humming it on the train.”

Solemn piano opened up for a strident alto saxophonist soon joined by bass and drums. The melody was barefaced and poignant. The shifting meters and ensemble’s expansiveness made for an interesting listen.

Steve: “This sounds like an Andrew Hill record.”

“Is it the pianist’s recording?” No - the saxophonist.

“Is it Rudresh (Mahanthappa)?” No.

“Is the saxophonist under 30?” Don’t know his age but he’s probably in the early to mid 30s.

The saxophone solo ratcheted the intensity to a boiling point.

“When the inspiration fails, you can always squeak.”

“Is it Jeremy Udden?” No, no… Definitely not.

The saxophonist was Darius Jones, a current critical favorite. His playing has been lauded for its power and bluesy soulfulness. The rest of the ensemble was made up of pianist Matt Mitchell, bassist Trevor Dunn and drummer Ches Smith.

Zak thought that this particular song could be deemed a “modern classic” as it had similar characteristics with Ornette Coleman’s modus operandi, a memorable melodic refrain and heart on your sleeve performance.

“Are the other tracks similar?” Yes. They are all a bit different but all have this very spiritual approach.

9. Bill Fay – “Methane River” from Bill Fay (Deram Nova DN 12, 1970)

Presented by Me – MP3 – Theme: C

I explained that during my tenure at Downtown Music Gallery I was privileged to hear a ton of music that I probably wouldn’t have otherwise. I spent a ton of time with Bruce Gallanter and Manny Maris and their wide, wild musical tastes.

It was Bruce that turned me on to this fairly obscure figure in the English folk music scene.

It was Bruce that turned me on to this fairly obscure figure in the English folk music scene.

I am not a tremendous fan of folk or folk-rock music but this recording totally put me under its spell. Most likely it probably had to do with the jazz elements of the larger ensemble.

“Methane River” was a pretty heady tune. It had Baroque pop leaning and a stout brass section. There was also a very blatant message of overcoming your obstacles with a very strange allegory – swimming a methane river?

Richard: “I think someone left his cake out in the rain…”

Richard thought it sounded similar to another British folk/pop songwriter, Al Stewart. I could hear the similarities but while Stewart chased a more pop and progressive rock base, this artist remained in an older style of popular song mixed with tinges of jazz and classical elements.

The artist was singer/songwriter Bill Fay. He recorded two albums for Decca’s Deram Nova label in 1970 (Bill Fay) and 1971 (Time of the Last Persecution). The albums sold poorly and Fay was dropped by the label.

It has taken some time and some reissues for Fay to gain some attention again. Both of his studio recordings were reissued in 2005. Live recordings of his Bill Fay Group were also released shortly thereafter. These featured the guitar of jazz/prog rock guitarist Ray Russell.

Steve: “Who did the arrangements on this record?” Michael Gibbs.

“Ah… Mr. Deram himself.”

Gibbs was a trombonist and go to composer/arranger for many projects during the late 1960s and 1970s.

Fay has begun a sort of comeback. He released a double CD collection in 2010 that featured a recording from the early 1970s that was never released alongside a collection of new songs. Fay has scheduled a release of a new album in the fall of 2012, as well.

10. Hiromitsu Agatsuma

Presented by Oran Etkin – YouTube – Theme: C

Oran wanted to present us a musician that he felt was completely “out of left field.”

The instrument that we heard was obviously of Asian origin. No one could place what it was or where it was from.

It turned out to be the Japanese shamisen, actually a larger version called the Tsugaru-jamisen, played by the virtuoso Hiromitsu Agatsuma.

Agatsuma has been well known for his use of the traditional three-stringed instrument in a variety of modern settings along with numerous collaborations with musicians across genres and cultures.

Oran said that he “needed to get in a comfort zone” with this music as he was going to be performing with Agatsuma in July. Apparently, he would be flying to Japan two days prior to their performance for a few quick rehearsals then a large concert. The band would include taiko drummers, piano and Oran on reeds.

“Playing this instrument with piano might be a misstep…”

“Reminds me of banjo picking. I could definitely see Bela Fleck ripping this guy off.”

11. Brad Paisley – “All I Wanted Was A Car” from 5th Gear (Arista Nashville, 2007)

Presented by Richard Gehr – MP3 – Theme: C

Richard had a mischievous look in his eye as he came forward with his iPod: “This was definitely out of my comfort zone when I first heard it. Now I love it.”

We had just gotten our first taste of twanging guitar new country and the gut-busting engine rev when Steve asked: “Does this fit in the realm of guilty pleasure?”

Richard: “I don’t necessarily like that term. I do like it, though.”

We kept listening, though. Our new motto: Give it a chance, give it a chance.

Steve: “Brad Paisley, right? I hadn’t heard him but I know he’s supposed to be a good guitarist.”

Richard: “A good songwriter, too.”

Steve: “Okay… But could the production get any more antiseptic? He is a good guitarist, though.”

“Yeah. The solo could have been about four minutes longer!”

Richard: “I think he’s better than Springsteen. (Some raised eyebrows there), His songs touch on real emotion and topics that are easy to identify with. Plus you can never be surprised by the literalism in country music.”

Richard had gone to see Paisley perform at Madison Square Garden.

“It was like a tribute to ADD. He was running around stage - taking huge solos in front of video projections and huge light shows. It was great. Anyway, it is the only commercial country music I can stand. “

Don’t know that I or any one else could agree.