Winter has been slowly creeping to its close. The ups and downs of temperature during February had made for a pretty unpredictable forecast for Sunday, February 24th. Though damp the day before, I was happy to find it a dry and fairly mild afternoon. Thus, the hardware lugging wasn’t unbearable.

BYOV #19 was held that February afternoon at Barbès in Brooklyn.

We had a pretty intense crew this time around and a ton of music was heard and discussed. Actually, some of these tracks have been fairly hard to come by. I’ve managed to work it out, however.

Our themes were:

a) Alpha and omega. We want to hear recordings from the beginning and the end of an artist's career to marvel at their scope.

b) The odd couple. Let's hear successful matchups between unexpected partners.

c) 1980s. The years of Reaganomics, big hair and leg warmers (apparently) had their ups and downs. Let's hear your favorite music from the '80s.

1. Audio Letter – “Fading Green” from It Is This It Is Not This (Neti-Neti) (CNLF-1, 1988)

Once again I led the charge with a selection that was both an unexpected matchup between musicians and a product of the ‘80s.

The listeners heard a solo percussionist joined by some samba whistles, drone-y female vocals, and gamelan-ish percussion. There were some ethereal guitar twangles, too.

Clifford: “This reminds me of the band Noh Mercy.”

It wasn’t the San Francisco based art rock/post-punk girl group. Though, this would prove to be fairly close both in spirit and physical proximity.

“Is this a singer playing all instruments or a singer with a band?” It was poet/singer with an ensemble.

“She’s getting her cues from Lydia Lunch.”

Clifford: “Is Robert Quine on this?” The former Voidoid and open-minded guitarist was not on this record. Though looking at his discography, this really seemed to be a good guess.

The odd ethnic blend wasn’t providing anyone with any inkling.

I gave a hint: “There are two women and two men.”

Nada.

“It is the women’s band.”

Crickets.

“There are two jazz musicians here. One should be considered a legend.”

Jason: “Don Cherry?” Yep. Don was present, likely on whistles and berimbau. He was also credited with trumpet, flutes, and Doussn’ Gouni on the record.

“Is it Latif Khan?” No. The tabla player, who Cherry collaborated with on Music / Sangam (Europa Records JP 2009, 1982), was not involved.

The other jazz musician was percussionist Denis Charles, phenomenal player originally from the Virgin Islands, who had played with many luminaries of the avant-garde, including Steve Lacy, Billy Bang, and Cecil Taylor.

“Oh yeah. Charles sounds just like he does on those Cecil Taylor records.”

The group was called Audio Letter, originally spelled as Audio Leter. The group was made up of two Seattle women, guitarist/improviser Sue Ann Harkey and poet/violinist Sharon Gannon. The two had made a number of cassette only releases on their Cityzens for Non-Linear Futures label. This was their first long player, which was recorded in New York in 1987.

This record certainly fit the multi-kulti element Cherry was working in at the time. We spoke briefly about his work with Bengt Berger, Rip, Rig and Panic, and his “rap” record, Homeboy (Sister Out) (Barclay 827 488-1, 1985).

2. Hans Dulfter and Ritmo Naturel ft. Jan Akkerman – “The Morning After The Third” from The Morning After The Third (Catfish 5C054.24181, 1970)

Not shy for his first time up to bat, Clifford dropped the needle right away. We heard a lone, mournful tenor sax, which was joined by a tempered bass and then not-so-tempered Afro Cuban percussion.

Clifford told us that there were two individuals in the ensemble who wouldn’t typically play together.

The hint was that the guitarist was a “ringer,” while the saxophonist was not.

“What year was this?” 1970.

Mr. Allen was generous with the hints.

“The saxophonist should be better known.”

We continued to listen to the burly toned sax over the bed of percussion.

“They aren’t American…?” No. They are mainly Dutch. One of the musicians is from Surinam.

With a hint of sarcasm aimed at the vamp, Steve: “They certainly like this chord.”

Clifford: “The guitarist hasn’t popped out yet, but he will.”

Then we heard the very electric, shredder on a very long terse solo.

I guessed that this was saxophonist Hans Dulfer. I hadn’t heard his music before but was able to weed him out from the typical Dutch crowd.

From there, the guitarist’s identity quickly fell into place.

“Is it a Dutch guitarist?” Yes.

Steve: “Jan Akkerman?” It was the progressive rock/fusion guitar master. He was already a member of the well-known Focus ensemble when this record was released. Definitely not the same feel.

Dulfer had begun performing professionally in the mid-1960s. He recorded with free jazz legend Willem Breuker and Theo Loevendie before he recorded his first album with Ritmo Natural, The Morning After The Third, in February 1970, followed by Candy Clouds (Catfish 5C 054.24.307, 1970), recorded in August 1970. He continued in this free meets Afro-Cuban vein, performing alongside Frank Wright, Roswell Rudd, and Bobby Few. Later, Dulfer’s work edged more and more toward mainstream, pop jazz.

Dulfer’s name was vaguely familiar to some of the listeners. It wasn’t his forays in free jazz, fusion or funk that were familiar to the listeners, however.

Me: “He’s Candy Dulfer’s father.” Ahh….

He was indeed the father of the smooth jazz, superstar sweetheart.

While the music might not have been to everyone’s taste, Dulfer’s tone made an impression. Clifford remarked that he had a grown up listening to many of the blues/jazz saxophonists of the 1950s, like Ike Quebec.

I thought his sound was reminiscent of the big voiced tenors of George Adams, Pharoah Sanders or Gato Barbieri (maybe it was the Afro Cuban accompaniment that made me say it?). Safe to say that Dulfer’s musical trajectory was similar to the Argentine saxophonist’s, too.

3. Etienne Brunet / Fred Van Hove – “Improvisation 1” from Improvisations (Editions Saravah, 2000)

Jason brought in a duo recording done by what he thought was an unusual pairing of musicians and instruments.

“There are three long tracks. Play the first one. It gets to it more quickly.”

Robert: “Is that an organ?”

We had heard the deep rumbling of a large pipe organ, which was met by a soprano saxophone.

Steve: “So this is Steve Lacy and who?”

Actually, this wasn’t Lacy on soprano this time.

“Is it all improvised?” Yes. All the pieces on the recording were improvisations.

“Was this actually recorded in a church?” Yes.

Steve: “It can only be European.”

He was right.

This piece was recorded at The Church of St. Germain-des-Prés in Paris during June 1997.

Jason mentioned that one of the musicians was a free jazz musician in his 70s.

Clifford was able to guess Belgian keyboardist Fred Van Hove.

Jason introduced us to his friend, Frenchman Etienne Brunet. The saxophonist had studied with Steve Lacy when Lacy had just moved to Paris in the late 1970s. The story was that Brunet plastered the city with fliers for Lacy concerts in exchange for lessons.

Brunet has shown a wide range of interests. He has recorded free improvisation, electronic compositions, and rock music. Brunet has even found an attraction to Romanian traditional music and has recorded some. Here is a link to Brunet’s website.

4. Shirley Horn ft. Miles Davis – “You Won’t Forget Me” from You Won’t Forget Me (Verve 847 482-2, 1991)

The next selection was another odd couple, at least for the time it was recorded.

Steve: “Yes. It is who you think it is."

Once we heard that plaintive trumpet call, Clifford: “Miles.”

We heard a supple female vocalist accompany the trumpeter (or visa versa) over a spare accompaniment.

Robert: “Oh…. I know. Shirley Horn.”

It was Horn’s recording of Goell and Spielman’s “You Won’t Forget Me” from the 1990 Verve album of the same name. The album was Miles’s last session as a sideman.

Steve mentioned that it would have been more and more unlikely to hear late Miles playing in this fashion. The trumpeter was more involved with an electric sound with elements of pop during the late 1980s and 1990s. This was a return to an entirely acoustic jazz setting.

It turned out that Miles was partly responsible for Horn’s success early on. He had heard and liked a couple of early recordings of Horn’s and he recommended her for a gig at the Village Vanguard. Miles’s clout helped to push Horn’s career forward.

Producer Richard Seidel had provided an interesting fact about this session to Steve. Apparently, Miles wouldn’t record live with the ensemble, so everything he did was overdubbed after the fact.

Steve: “It’s great anyway.”

We laughed at the thought of the rhythm section comping nobody during Miles’s solo.

“Even weirder is Miles playing with Scritti Politti.”

Miles had recorded with the British new wave group in 1985, alongside Roger Troutman and Marcus Miller, for a tune called “Oh Patti (Don’t Feel Sorry for Loverboy).”

Clifford: “Miles sounds like himself. Relaxed.”

It was intriguing to hear the continuum between the sound that first delivered Miles’s popularity in the 1950s still being available to him in the early 1990s.

As we kept listening, Steve: “She is the vocal equivalent to him.”

Robert: “I wouldn’t have thought he had it in him to be so restrained.”

Pop quiz: Who was another vocalist Miles worked with?

Miles appeared on Bob Dorough’s “Blue Christmas.”

5. Bud Powell – “Dance of the Infidels” from The Amazing Bud Powell, Volume 1 (Blue Note BLP 1503, 1955 (1948))

Bud Powell – “Dance of the Infidels” from The Lonely One (Verve MG V-8301, 1959)

Robert was the first to tackle the beginning and end of an artist’s career theme. He felt that the selections might be a little conservative to our ears, though the changes from the beginning to the end of this player’s career he found very unusual.

We heard a snappy two-horn introduction that led to a solo piano melody quickly rejoined by the horns.

Steve: “Sonny Rollins’s ‘first session.’ In 1949. But it really wasn’t his first session.” Rollins had recorded an earlier session with Babs Gonzales before this recording in August.

Jason: “Was this Sonny’s date?” No. It was pianist Bud Powell’s first recording for Blue Note for the Amazing Bud Powell Vol. I release. This was the quintet version of “Dance of the Infidels,” which featured Rollins, Powell, trumpeter Fats Navarro, bassist Tommy Potter, and drummer Roy Haynes.

Powell had already made a name for himself during the 1940s as a gifted modern during the inception of be-bop. The recording was made a few months after Powell was released from Creedmoor State Hospital where he received electro shock therapy to deal with his aggressiveness, especially apparent while drinking. He was later diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Clifford: “Rollins in ’49 sounds like Archie Shepp in 1963.”

Robert then played a later version of “Dance of the Infidels” from the 1959 Verve release The Lonely One. The recording was actually made in 1955 and featured bassist Percy Heath and drummer Kenny Clarke.

Though this wasn’t at the end of Powell’s career, the recording really showed the deterioration of his playing.

Robert: “To my ear, this is not as good as the first recording. It just proves that later is not always better.”

Powell moved to Paris in 1959 and continued to play and record spotily through the early 1960s. His chops continued to wane, as did his mind.

Robert: “He just began to run out of ideas.”

Steve: “Well, by this time he was seriously disturbed.”

Clifford: “I do remember Bud having flashes of brilliance toward the end on those Fontana releases.” These were extremely late releases from 1962 to 1964.

Robert: “But it was harder. What a sad story.”

Powell died in 1966 from complications from his contraction of tuberculosis three years earlier and neglecting his health.

Robert remarked about how interesting it was to see musicians get where they were going.

“Paul Chambers was great at 19 years old.”

Zak looked back with admiration at that generation and their work to try to achieve something.

“They were living poorly. They really had to work if they really wanted to make a mark.”

For Jason, leaving a mark started with having a sound or developing one.

Clifford: “Yeah. Listen to late Ben Webster.”

Further, Clifford was friendly with the late trumpeter/conceptualist Bill Dixon and said that Dixon really let his limitations shape his own sound and musical conception.

Steve speculated that if Thomas Heberer had been in the house, we would have likely heard Clifford Brown. Thomas?

6. Michael Hedges – “Aerial Boundaries” from Aerial Boundaries (Windham Hill WD-1032, 1984)

Next up was another slice of the 1980s.

David told us that the performer was principally an instrumentalist but later became a vocalist as well. He also passed away in the late 1990s.

Before the music, Steve: “James Chance?” Ah, no. By the way, Chance definitely isn’t dead.

The reverbed acoustic guitar was far from James Chance. It was a nice listen, though.

Steve: “Is it D. Boon?” No it wasn’t the guitarist and former member of the Minutemen. Boon had passed in 1985 in a van accident.

Steve wondered if I knew who it was, as I’d been on an acoustic guitar kick. I said no but I was interested to find out.

Steve then guessed that it was Michael Hedges.

“The white guy with the dreads, right?” Yep.

Originally from Sacramento, California, Hedges was a classically trained guitarist who graduated from the Peabody Conservatory. He moved to Palo Alto to attend Stanford but was discovered by pianist William Ackerman who quickly signed Hedges to record for his Windham Hill record label.

Hedges developed a unique and varied style on the guitar. He recorded a number of releases for Windham Hill before his death in 1997 in an automobile accident near Boonville, California. Maybe that was where the “Boon” arose? Steve?

Steve wondered where this strain of improvised acoustic guitars came from. He believed that John McLaughlin’s My Goals Beyond (Douglas KZ 30766, 1971) was highly influential to musicians like Hedges.

A few of us chimed in that acoustic guitar improvisations had been en vogue for some time through recordings made by John Martyn, Pentangle, Leo Kottke, and John Fahey. Some were very experimental in their approach, adding electronics and effects to their sound.

Steve asked David if he had seen Hedges live. He had seen him in 1988.

“He was a California guy?” Yeah. Really….

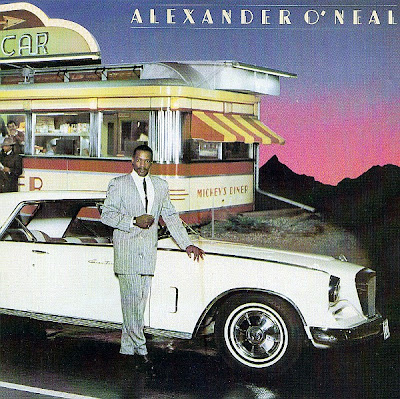

7. Alexander O’Neal – “What’s Missing” & “If You Were Here Tonight” from Alexander O’Neal (Tabu Records FZ39331, 1985)

In the introduction to his ‘80s musical selection, Zak was forthright:

“Being the resident R&B specialist and there is a ‘80s theme, there is something I just have to play.”

Then came the Linn drum.

Steve: “Are you sure this is the ‘80s?”

Sure there were punchy drums, washy synths and keyboards galore.

Steve: “I know this tune. Is it that Minneapolis guy…? Alexander O’Neal?”

Zak: “The production gives it away.” The producers were the Minneapolis masters Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis.

Originally from Mississippi, O’Neal moved to Minneapolis as a young man. He joined Jam and Lewis’s Flyte Time. The band was then signed to Warner Brothers with the help of the “Purple One” himself, Prince. O’Neal was dumped from the group and replaced by Morris Day, allegedly because he was “too black” (likely a money issue, in reality).

Steve: “Now he was a singer.”

Zak: “He was fucking great! But Prince fucked him over. But the ‘80s were still great for him. But in the ‘90s, he fell off.”

Steve: “If you couldn’t find any who could sing like this, these records would be nowhere. But somehow the music made the synthesizers vital.”

Zak played the slow jam “If You Were Here Tonight” afterward. We laughed at the lengths of the songs on the album. A bit overindulgent?

All this led to the inevitable question: “What’s the makeout music these days?” Possibly a future BYOV theme?

8. David Murray – “Ballad for the Black Man“ from Ballads (DIW Records 840, 1990 (1988))

As he plugged in his iPod, Steve told us that this was a recording by a musician who was “the emblematic guy of the ‘80s.”

“Here he is at his most conventional and it is great.”

We heard a lithe but brawny tenor sax in a quartet. The piano was especially flourishing.

Robert: “Yep. I know. But I won’t say.”

Jason: “It could be Archie.” It wasn’t Mr. Shepp, who had certainly done similarly contoured, restrained recordings during the 1980s.

We listened on with no names coming to us.

Steve: “People should be able to get this but won’t. It is David Murray.”

It was the über-prolific tenor player who had taken the 1980s by storm. Murray came through the 1970s with a high pedigree, making genre-spanning records for labels small and large. He had begun as an avant-gardist but in the ‘80s began to reach back to the roots of the music.

On this 1990 Japanese release (recorded in 1988), we heard the lyrical side of the musician with a great band including pianist Dave Burrell, bassist Fred Hopkins, and drummer Ralph Peterson, Jr. The recording was made up of ballads written by the ensemble, most by Murray.

Clifford: “It is hard to be the man. He was able to make to many records making it hard to sift through.”

He was right. The over production of product may have watered down what should have been the desired effect of his obvious ability. Some of us argued that the same could be said of Steve Lacy or Anthony Braxton.

Jason objected a little: “Those guys were launched further as composers. I wouldn’t guess this was Murray. He was Ben Websterizing.”

Steve: “I understand the composer idea but Murray wrote some great songs. Like this one.”

Clifford: “Same with Burrell. Like his tune, ‘Margy Pargy.’” This was on his Douglas debut album, High (SD 798, 1968) – which featured a side long rendition of the West Side Story theme by Leonard Bernstein - and later on his “big time deal record” on Arista Freedom, High Won – High Two (AL 1906, 1976).

9. The Free Spirits – “Don’t Look Now (But Your Head Is Turned Around)” from Out of Sight and Sound (ABC Records 593, 1967)

Jim Pepper – “3/4 Gemini” from Dakota Song (Enja 5043, 1987)

I also decided to try my hand at the “alpha and omega” theme.

Robert: “Are you playing the first first or the first last?”

Me: “Huh? Oh, first then last.”

A wild mélange of surf rock, soul and free jazz spilled from the speakers.

“Are we listening for an individual or the group?” An individual in the group.

We continued to nod through.

“Which instrument?” The saxophonist. Not in the forefront but definitely taking space when wanting to.

“The musician is no longer alive?” Right.

No one was able to guess from the first selection, so I threw on the second.

A lone tenor sax echoed through the room. The horn was then joined by a swinging rhythm section, as they spun into the melody of a jazz waltz.

Clifford: “Jim Pepper?” Yes. The Native American tenor saxophonist who had popularized “Witchi Tai To.”

The first piece that I played was the lead off track “Don’t Look Now (But Your Head Is Turned Around)” written by guitarist Larry Coryell for the proto-progressive rock band, The Free Spirits. The band also included bassist Chris Hill and drummer Bob Moses.

This was the first recording of Pepper. He would go on to be a member of Hill’s Everything Is Everything group, where he first introduced his “hit” “Witchi Tai To.” Pepper would record in this vein of rock/jazz/folk through his own debut in 1971, Pepper’s Pow Wow (Embryo SD 731, 1971).

Though he worked through the 1970s, Pepper was absent from recording until the beginning of the 1980s when he worked with Charlie Haden’s Liberation Music Orchestra (The Ballad of the Fallen, ECM 1248) and on a handful of Paul Motian recordings.

The second recording we listened to was Pepper’s 1987 recording on Enja which featured pianist Kirk Lightsey, bassist Santi Debriano, and John Betsch. It wasn’t his last record but was near the end as he passed away in Portland on February 10, 1992.

I was asked where my favorite Pepper playing showed up. I mentioned his recording with Motian as probably the most interesting material, Jack of Clubs (Soul Note SN 1124, 1985) stood out in my mind.

10. Burton Greene – “Ballad Two” from Burton Greene Quartet (ESP Disk 1024, 1966)

Burton Greene – “Tree” from Live at Kerrytown House (NoBusiness NBLP 49/50, 2012)

Clifford also decided to try his hand at the same theme.

We heard a restrained piano accompanied by a strident alto saxophone. The rest of the quartet came in quietly. The arrangement was spare.

Me: “That saxophonist has quite a tone….”

Steve: “Is the performer well known or fairly obscure?” Obscure. The pianist is the leader and the musician in question.

We continued to listen.

Steve: “Who was the Georgia Faun? Marion Brown?” Yes. It was the great, recently departed alto player.

Jason: “Burton Greene.” This was from his debut album on ESP Disk’ that was recorded in 1966. Along with Greene and Brown are bassist Henry Grimes and drummer Tom Price.

“Is this representative of the oeuvre?” Yeah. Sort of. I didn’t want to blow the lid off the place.

We spoke a bit about Greene’s approach to the music here. There was a tinge of Tristano’s touch in his playing. Also, a bit of classical.

Clifford also mentioned the negative attention that Amiri Baraka (then LeRoi Jones) gave Burton in his book, Black Music. There, Baraka wrote about musicians knowing and searching for the spirit in their music. He wrote specifically about a concert where Burton was pitted up with Brown and Pharoah Sanders. While the saxophonists blew to oblivion, Burton, apparently, was unable to reach their shared state of ethereality and resorted to overindulgence by beating on the piano in search of the spirit. Whatever….

Perhaps Baraka was being a little unfair because Burton was white? Maybe his inspirational spirit told him to bang on the outside of the piano?

Anyway…. I digress.

There was also the observation that Henry Grimes would have also been playing with Sonny Rollins at this time. He also recorded on Roy Haynes’s Out of the Afternoon (Impulse! A-23, 1962), four years prior. Here Grimes was at his more out, for sure.

Clifford then put on a recent solo recording from Kerrytown, Michigan in 2010. This was a performance at the highly regarded Edgefest held there every year.

Clifford assured us that Burton wasn’t dead, this was just later work. As a matter of fact, the pianist has wanted to move back to the States and find gigs in New York. Burton moved to Paris in 1969 and has spent the majority of his life in Europe.

His style wasn’t nearly as related to the style of free piano associated with Cecil Taylor. This was a more subdued and lyrical approach, though he could stretch out.

Robert: “I hear more of a continuity between the early recording and the last one.”

Jason mentioned Burton’s performance on Patty Waters’s Sings (ESP Disk 1025, 1966) and College Tour (ESP Disk 1055, 1966), where he had be pushed to play farther and farther out. He was even heard tossing garbage pail lid on Sings.

Apparently, Burton hadn’t enjoyed playing with Waters. He felt that her music had been too much like lounge music.

It was also interesting to note that Ran Blake appeared on Waters’s College Tour recording. Steve felt that Burton and Blake shared a similar style, though Blake has been a bit more concise in his performances.